Rest in poems, Niall McDevitt (1967-2022)

The poet Niall McDevitt — a founding member of New River Press — has died on 29th September, aged 55 at home in North Kensington after six years lived with cancer. He was a restless presence in London poetry. A serious poet and enthusiast of other poets. Iain Sinclair, Yoko Ono, Patti Smith, and John Cooper Clarke all admired his work. The literary walks McDevitt gave, ‘psychogeographic investigations’, saw greasy cafes and elite hotels alike as places of poetic pilgrimage. Jeremy Reed, an older contemporary who influenced McDevitt’s early style, described him as ‘a luminous custodian of the great poetic mysteries’, adding that ‘London will never be the same without him’.

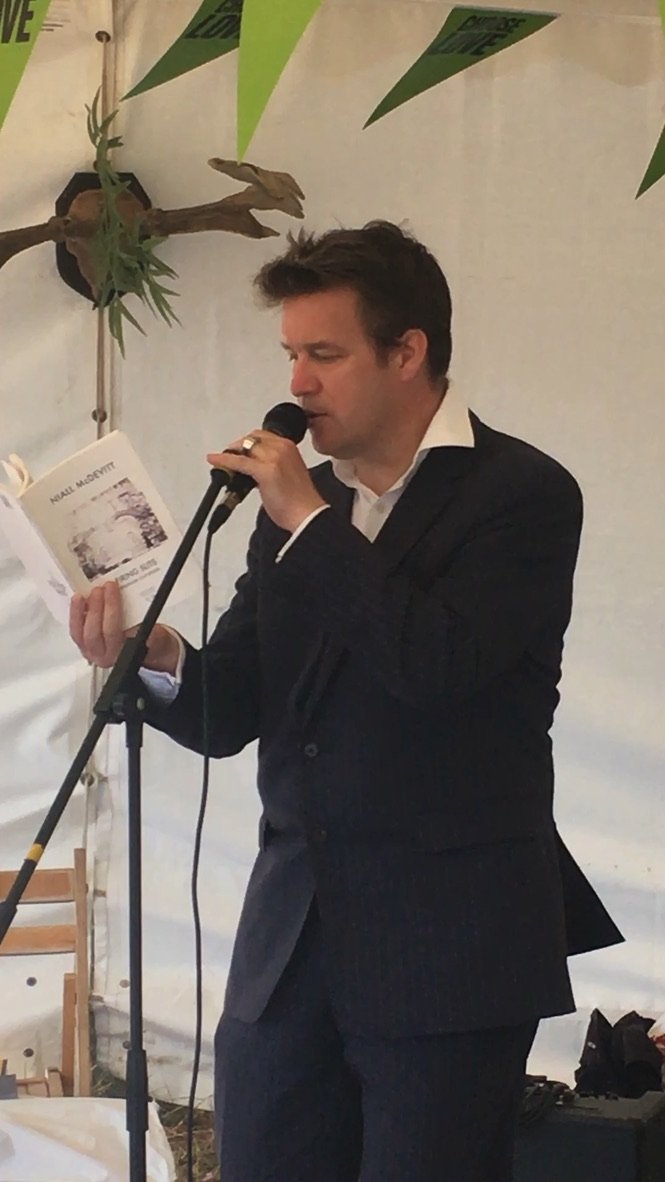

McDevitt dedicated his life to poetry, to a Blakean vision that celebrated freethinking and resisted the rule of the philistine establishment. His poetry is by turns solemn and sage, with a melancholic romance, or in the words of Heathcote Williams, ‘savagely witty’. A charismatic and sometimes provocative performer with a low, booming voice, McDevitt was more acutely perceptive than first appeared. His loyal, scrutinous attention championed the creativity of all he met. With uncomplaining dignity, he lived to the full while ill. Only four days before his death, McDevitt visited the grave of Victorian poet Algernon Charles Swinburne in Bonchurch, Isle of Wight. Though wheelchair-bound, beaming with delight, he mustered a lecture on Swinburne’s colourful private life and advocacy for Blake.

McDevitt brought many to the path of poetry. A Londonist who led highly original literary walks to uncover traces left by great world writers on the city, in particular the four McDevitt called his ‘personal Kabbala’: Shakespeare, Blake, Rimbaud, and Yeats. His ‘wandering lectures’ revealed a whirlwind of history on unassuming streets. An industrial alley behind The Savoy is shown to have been set ablaze in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1377; to have witnessed the death of William Blake in 1827 and Bob Dylan giving birth to the music video in 1965 in Subterranean Homesick Blues.

The product of six years’ work, London Nation returned from the printers on the day McDevitt died — just in time for the poet to hold a copy. The golden hardback shows Thomas De Quincey with ‘Ann of Oxford Street’, who reputedly once saved the young De Quincey’s life with smelling salts. The paintings are by artist Julie Goldsmith, McDevitt’s partner, collaborator, and now literary executor. Goldsmith and McDevitt made a glamorous pair in pinstripes and leopard print. To Goldsmith’s son, Heathcote Ruthven, McDevitt was a devoted stepfather, responding to, without fail, everything the younger writer wrote. Ruthven and McDevitt worked closely to programme McDevitt’s London Poetry Walks and, with artist Robert Montgomery, design and edit Niall’s work for New River Press. Their Portobello Road address became a loving home and space for McDevitt to develop his work to more critical acclaim. In early 2022, McDevitt was ecstatic to sign a deal with Cheerio books, an imprint of Hachette backed by the Estate of Francis Bacon, for a book about Geoffrey Chaucer.

McDevitt’s poetry wove diverse traditions to unique effect. In a hymn to the murdered playwright Christopher Marlowe, he beats a Celtic Modernism on a Bodhrán drum to the underbelly of Elizabethan England; London Babylon adapts Ancient Sumerian texts to critique contemporary neoliberalism; Firing Slits: Jerusalem Colportage, the result of a summer in Palestine, fuses two of McDevitt’s lifelong preoccupations — the culture of Judaism and the Jerusalem of Blake — to create a startlingly original world of haunted hopes. Though dense with history and religion, McDevitt’s work is decidedly unacademic. He learnt from Joyce and Chaucer how to remain alive to the visceral contemporary, sing to the music of diverse voices, and travesty piousness with scatological wordplay. McDevitt found in London a lodestar to make vast libraries of erudition concrete and immediate.

Born in Limerick in February 1967, McDevitt moved to South Dublin as a child. Unusually for Seventies Ireland, Niall and his siblings Roddy and Yvonne were raised by a single father, Michael, a famously good-looking man who worked for Irish Rail. After separating from the family, Niall’s mother, Frances, from a distinguished Irish musical family, emigrated to London, where her three children separately followed suit.

McDevitt was educated at the Jesuit-run Belvedere College and University College Dublin. Like fellow alumni to both schools, James Joyce, McDevitt excelled in a Classical Latin education the richness of which is enshrined in his writing. ‘Bloomsday’ walks, following the path of Leopold Bloom in Ulysses, was founded in 1954 by a friend’s father, the artist John Ryan. Discovering the tradition was ‘extra-curricular manna’, said McDevitt. ‘It showed how a literary walk could become a national holiday.’ Unknown to him then, Bloomsday became a model for the mode of research McDevitt would develop for the rest of his life.

In 1996, McDevitt’s poem ‘Off-Duty’, describing a drunk clinging to a lamppost, was selected by Roger McGough to be shown on the 38 and 73 bus routes for a year, part of the ‘Poems on the Buses’ project by Transport For London. The selected poets were invited to read at St. James, Piccadilly. This proved fateful for the 29-year-old McDevitt. At the Grinling Gibbons font where Blake had been baptised in the 1750s, McDevitt sang ‘London’ and felt the human Blake come alive. This ignited a hunger to seek out other Blake sites, found at first through Paddy Kitchen’s Poets’ London (1980). Soon, McDevitt was discovering new sites. By 2006, his weekly William Blake Walk was a well-known fixture, featured in journalist Nigel Richardson’s Great British Walks; on Radio 4’s The Poet of Albion, Robert Elms Show, and The Verb; and a BBC London documentary.

McDevitt came to London as an ‘aesthetic migrant’ in search of bohemia. He found his feet joining his brother, Roddy, in the troupe of countercultural impresario Ken Campbell, performing in Neil Oram’s 24-hour play The Warp. One role McDevitt played was based on poet Harry Fainlight, one of many under-acknowledged poets McDevitt organised nights for. McDevitt campaigned to secure poetic landmarks from redevelopment, once chaining himself with fellow poet Aiden Andrew Dun to the railings of Rimbaud and Verlaine’s home at 8 Royal College Street in Camden. McDevitt worked closely with Campbell on Pidgin Macbeth, a transposition of Shakespeare into the language of the Pacific island of Vanuatu, Bislama. Soon fluent, McDevitt became resident ‘Pidgin poet/translator’ on John Peel’s programme Home Truths, translating Yeats and Rimbaud into Bislama, and . McDevitt put the language to anti-imperial use: a 2003 Guardian report on right-wing historian Niall Ferguson reads: ‘Security men removed a self-styled "shamanistic poet", Niall McDevitt, from the lecture, when he accused Prof Ferguson of trying to "alleviate guilt", while reciting a poem in pidgin on the imperial legacy in the New Hebrides islands in the Pacific.’

During national lockdowns, director Sé Merry Doyle made films of McDevitt’s ‘poetopographical’ walks. An infamous daemon-summoning duel between Yeats and Alistair Crowley is recounted in The Battle of Blythe Road, an incident McDevitt described in a poem in 2010’s b/w. Reluctant Groom explores the church where James and Nora Joyce married in Notting Hill. McDevitt met Doyle through Rosalind Scanlon, Cultural Director at the Irish Culture Centre, where McDevitt became poet-in-residence in the late Nineties.

In August 2021, McDevitt devised five new Blake walks, pairing Blake with Thomas Paine and Emmanuel Swedenborg, with the River Tyburn and Bedlam Hospital, and finally with the modern painter, Francis Bacon. Each walk is recorded in Doyle and Scanlon’s series Blakeland — films that will forever be essential viewing for serious students of Blake or London. In an emotional evening only two weeks before his death, McDevitt attended the full-house premier at the Portobello Road Film Festival for the first film, on McDevitt’s fellow republican, Thomas Paine. Given the recent death of Elizabeth II, the timing was apt. A frail McDevitt, still with his wits about him, declared in an introduction — ‘I’m glad to be living in a democracy again’.

Niall McDevitt is survived by Julie Goldsmith and her son Heathcote Ruthven, his mother Frances McDevitt, siblings Roddy and Yvonne McDevitt, and niece Dixie McDevitt.

McDevitt is the author of four poetry collections, b/w (Waterloo Press, 2010), Portaloo (International Times, 2013), Firing Slits (New River Press, 2016), and London Nation (New River Press, 2022).